I am hard at work this long weekend on the first chapter of my new book (or at least, the first one I’m writing). The book is a series of little essays on what a handful of women writers, intellectuals, and artists from the 20th century can teach us about feasting. I have about a dozen women on my list, and it’s not a very long book, so I am not extensively covering their biographies; instead, I’m trying to construct a picture of feasting that’s a little bigger than what I’ve typically read or heard.

I am not exactly sure how this particular idea came to me, except that I am very interested in the concept of feasting. Clearly some of that is thanks to my love of The Supper of the Lamb, which I have written about in this newsletter before — a book that’s explicitly about fasting and feasting, and about loving the world. But I also know that beyond that book, most of what I’ve read about this very natural, very beloved human activity has felt a little … shallow? Or maybe just repetitive. I have heard and thought about feasting as a communal activity, a celebration, and a reflection of hope of some future glory (at least in a Christian framework), but something in my mind won’t let go of the idea that there’s more to it than that.

Over the last year of thinking about it over and over, I keep coming back to one idea: that feasting is subversive, and revolutionary — a place where the powerful are laid low, where those who participate partake in something that challenges the man-made order of things. Obviously there’s plenty to draw on when thinking about this from several different religious traditions; I was startled this spring, while participating in two different Zoom seders hosted by Jewish friends, to remember just how much the Passover feast is about revolution and change and flattening the mighty. Or I think about my own tradition, in which feasts are ways for Jesus to make people question what they complacently believe to be true: that we ought only to associate with the holy, that a king could not become a servant of all.

But anyhow, most of the people I’m writing about weren’t religious, or didn’t fit the molds very well. I’m interested in hearing what they have to say.

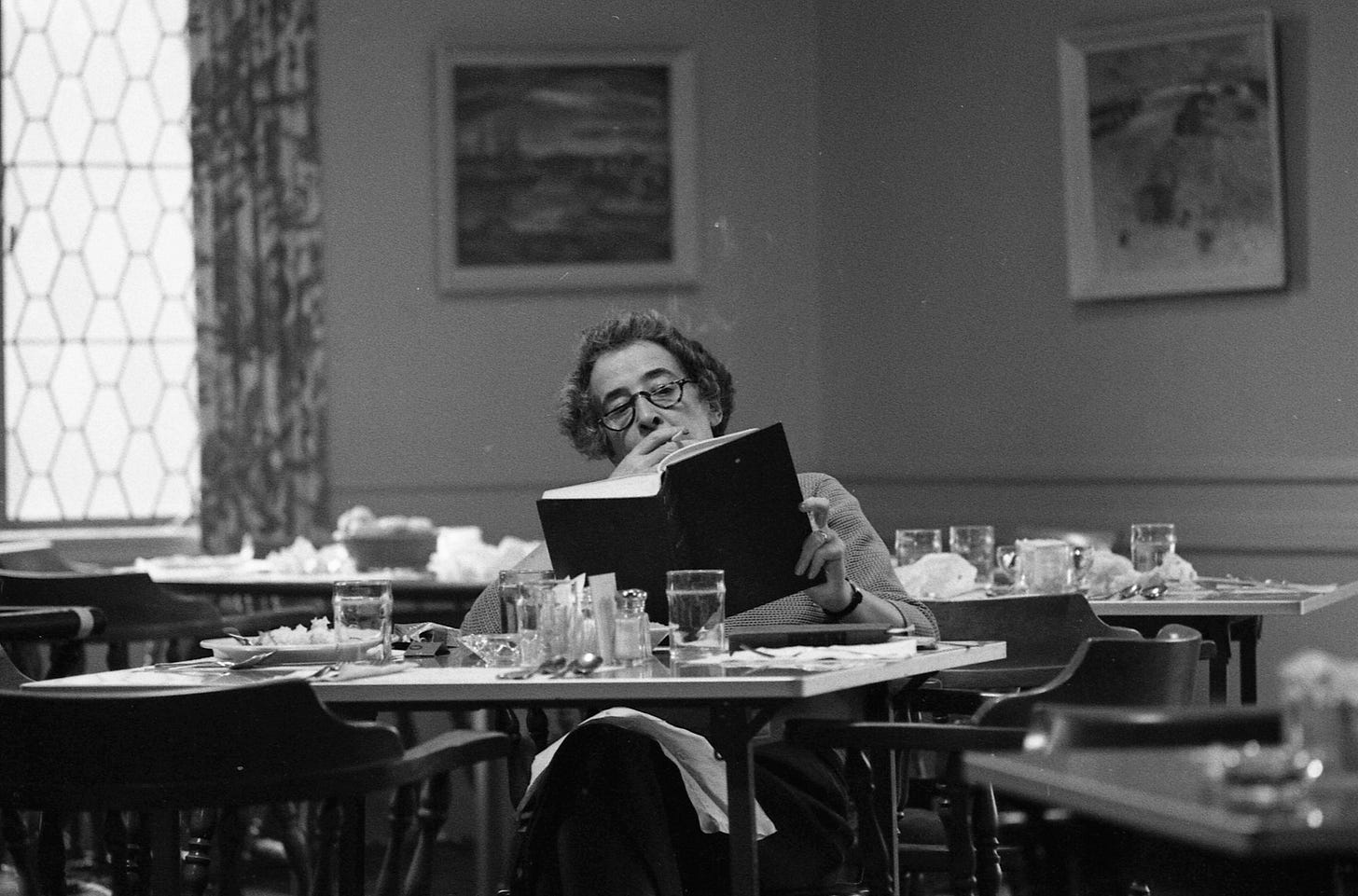

As I said, I have a list of women, but I have been aware ever since I started working on this that the central figure is Hannah Arendt. I’ve been reading her and thinking about her for months — years, really, since I took a course on The Origins of Totalitarianism last fall, and have subsequently read a lot of books about her, and read The Human Condition this spring, which blew me away.

I am trying to circle around to what I think she has to teach us — and of course I don’t want to give my secrets away. But one thing that Arendt always wrote about is “plurality” as fundamental to the human condition. What she meant was that we are each distinct from one another, and we can only love one another in our distinctness. She did not really believe in loving abstract categories of people — like “women” or, in her case, “the Jews.” She believed you could have regard for and fight for and insist on the dignity of groups of people, simply because they were human.

But loving someone, if I read her correctly, is something you can only do because someone is themselves. The body they were born into, with its various markers and characteristics. The life they lived. Their personality. Their likes and dislikes and proclivities and talents and deficiencies.

That led her to value friendship in particular as a bridge between the private (your family and your home) and the public (where we go to be citizens and to interact with one another). Friendship is, for her, a place for two people to become more of their particular selves, to become more individual. Friendship is where we test out the truth of our opinions, where we work them out in conversation, where we practice thinking, which Arendt says can only be done in conversation. (For her, the act of thinking alone is the act of being in conversation with yourself.)

This thinking thing is so important to her — and I kind of love it. In writing about Eichmann, who engineered the Final Solution and was responsible for the deaths of millions of Jews, she developed the notion that it is failure to think that makes us sub-human and susceptible to doing evil.

When she wrote about the “banality” of evil, what she meant, as far as I can tell, is that we can do evil without “intending” to, without having evil motives. In fact, it is precisely the lack of thinking about it that makes us susceptible to living within systems that have evil baked in. Those who cooperated with the Third Reich and the extermination of the Jews in the Holocaust could plausibly claim (as Eichmann did) that they were just following orders, or just doing what they were supposed to do; Arendt says that evinces that they surrendered the capacity to think for themselves, and, thus, their humanity.

Where we learn to think is our friendships, and she doesn’t really mean we have to be friends with people on “the other side,” as we’re so fond of saying these days. She simply means that our friendships are where we, in love, test out our ideas on someone else. Sometimes they will disagree, and sometimes they will agree but sharpen us, as her closest friends usually did.

What does all this have to do with feasting? I think it may be fair to say that a meal becomes a feast when it is among friends, and Arendt tells us that requires the act of thinking. Much of her thinking happened at dinners and cocktails with her friends (and her husband, Heinrich Blücher, who was as much her friend as her partner). There is something in the act of sharing the basic thing of the world — food and drink — with others that encourages thinking; I’m not sure she ever said this outright, but her basic principle, amor mundi (love of the world), was predicated on the idea of encountering the world as it is, with its horrors and triumphs, and trying to understand it, and thus it makes sense that the most basic worldly thing of eating and drinking would be where this begins.

That’s all a little dense, and I’m going to try to make it less so (and bring in quite a bit of Mary McCarthy’s friendship, I think). But I find it energizing to contemplate what she more or less says, and what many of my other subjects practiced: that the friendships forged over feasts turn the world upside down, and remind the powers that be, the ones that seek to deny our particularities and our lived experiences, that they do not get the final word.

This reminds me of a line in Wisława Szymborska's poem Possibilities: “I prefer myself liking people / to myself loving humanity.”

This is Canadian Thanksgiving Day and I just finished making a batch of applesauce (with Cortlands). Thank you for your thoughts out loud on friendship, feasting and Hannah Arendt. As we enter the season of shortening daylight, and more cocooning due to COVID -19, finding ways to do this (feasting, friendship as a way of thinking through) seems like one of the best challenges to our creativity. I'm looking forward to that challenge, and, to your forays in the coming months.