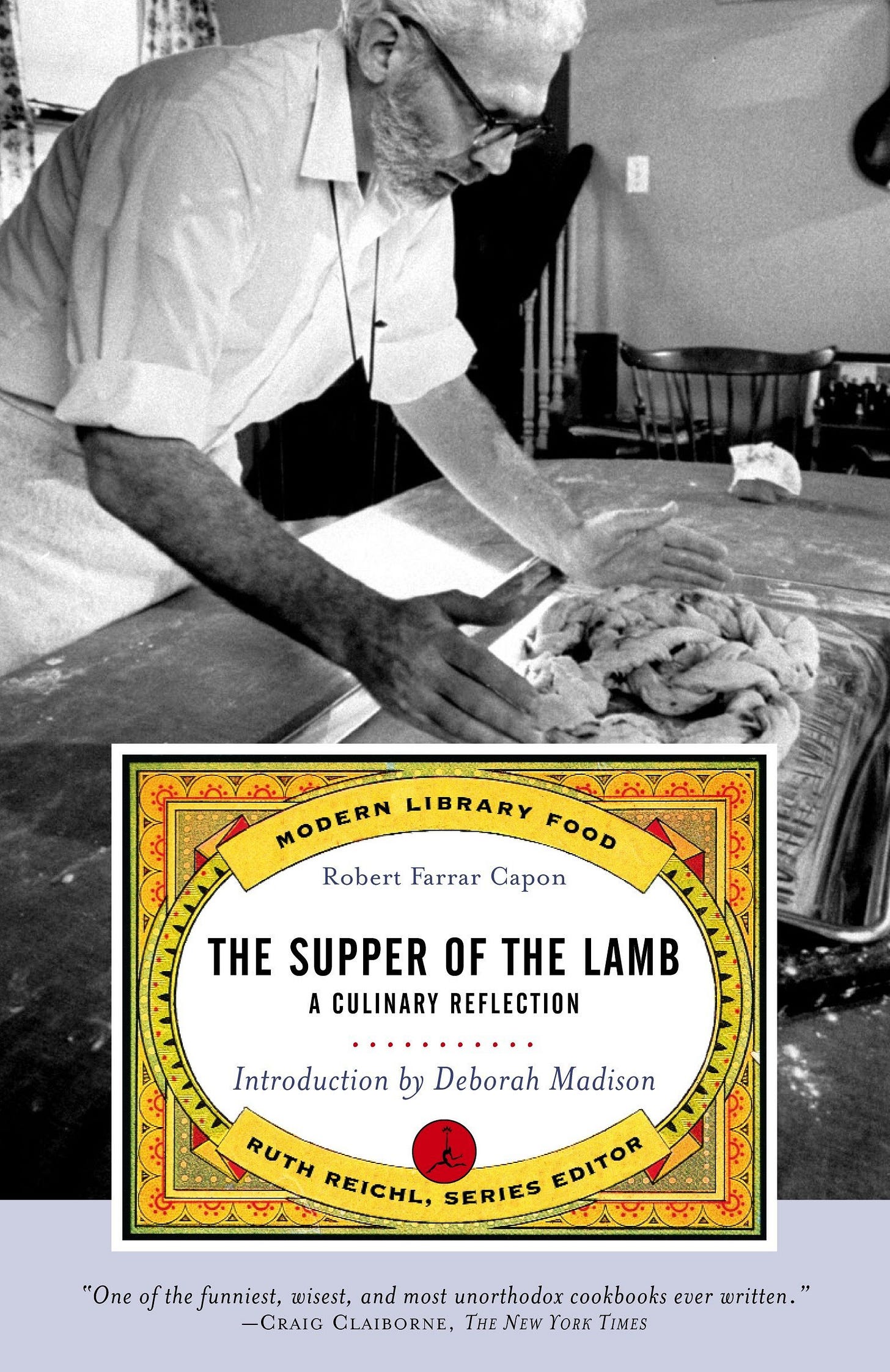

I have written many times about Robert Farrar Capon’s The Supper of the Lamb, which is truly my favorite book in the world, and the one that may be most responsible for my work, career, and general approach to life. I named my sporadic food newsletter for the book. Capon (who was an Episcopal minister and also frequently wrote about food for the New York Times) wrote the cheeky book — which the great food writer and former Gourmet editor Ruth Reichl selected for the Modern Food Library — as a way to talk about food and theology and creation and everything else. It is most certainly my favorite work of food writing, and probably of theology too.

The Supper of the Lamb has an organizing principle: Capon promises to walk the reader through his instructions for how to make Lamb for Eight Persons Four Times. But he keeps getting sidetracked (“The world is such an amiable place,” he says. “There is a distinct possibility that a properly attentive cookbook might never get through even one recipe”), and as a result, the book is more like a collection of interlocking stand-alone essays than any of the things one might expect it to be—theological treatise, sermon, self-help manual, cookbook.

Part of the reason he gets “distracted” so often is that he is pursuing an argument separately from the recipe, one that he lays out at the beginning of the book and then returns to repeatedly: that the created order is good, that God delights in it, and that Christians cannot be faithful (or good humans) without also delighting in it. This is important whether Capon is contemplating an onion, or exhorting the reader regarding knives, or scoffing at what he says are the “spooks” we call calories.

These digressions mean that it takes Capon sixteen chapters to get through the lamb recipe, each of which could almost stand alone as a single essay, each with its own discrete topic, from meat and knives and wine to pastry and parties. The lamb gets cooked, but only incidentally—by chapter nine, we’re still thickening a stew—“at long last (you have been patient),” Capon says, “I am ready to thicken the stew.”

Because I often get impatient with people who cannot stick to the topic at hand in conversation, I wondered why I didn’t get impatient with the structure of The Supper of the Lamb, and why I often forgot that there was a lamb stew simmering back on the stove, at least in Capon’s narration. How—and why—does The Supper of the Lamb work?

First, it is structured as a narrative with the reader as protagonist, and Capon addresses the reader directly:

Melt the butter in a pan large enough to hold the liquid easily, stir in the flour, and cook for a minute or so over low heat. Then pour most of the liquid from the stewpot into the saucepan and beat vigorously with a whisk, being careful to scrape the bottom and corners of the pan as it comes to a boil. When thickened, pour it back into the stew, stirring gently until well mixed. Continue cooking for a few minutes, correct the seasoning, and serve. Your stew, so long deferred, stands finally extra causas. Greet it as a fellow customer: It is as deliciously unnecessary as you are.

This direct address is familiar to those who read cookbooks, which like other instruction manuals are addressed to an often-implied “you”—you melt the butter, you pour the liquid. Yet Capon’s address to the reader steps beyond this familiar way of speaking and addresses the reader even more audaciously: “Your stew, so long deferred, stands finally extra causas . . . It is as deliciously unnecessary as you are.” The reader is part of an ongoing narrative, one in which Capon continually tells her what she is doing and what she will do next, and why. He returns to this at the beginning of every chapter, circling back to the matter at hand. One gets the image of a budding cook reading each chapter and following the instructions, then getting engrossed in the digression and letting things bubble and simmer while Capon pontificates playfully.

This holds the book together, providing a time-driven narrative. By involving the reader explicitly as a character in his narrative, Capon keeps his reader engaged where otherwise she might feel as if he is preaching or merely musing aloud for his own benefit. While each chapter, with a few tweaks, might work as a discussion of a single topic on its own, stringing them together with this narrative provides a backbone upon which the topics can build an argument about the goodness of the created order—and keep the reader interested.

I leave you with my favorite passage:

The world . . . is a gorgeous old place, full of clownish graces and beautiful drolleries, and it has enough textures, tastes, and smells to keep us intrigued for more time than we have. Unfortunately, however, our response to its loveliness is not always delight: It is, far more often than it should be, boredom. And that is not only odd, it is tragic; for boredom is not neutral—it is the fertilizing principle of unloveliness.

There, then, is the role of the amateur: to look the world back to grace . . .

. . . Peel an orange. Do it lovingly—in perfect quarters like little boats, or in staggered exfoliations like a flat map of the round world, or in one long spiral, as my grandfather used to do. Nothing is more likely to become garbage than orange rind; but for as long as anyone looks at it in delight, it stands a million triumphant miles from the trash heap.

That, you know, is why the world exists at all. It remains outside the cosmic garbage can of nothingness, not because it is such a solemn necessity that nobody can get rid of it, but because it is the orange peel hung on God’s chandelier, the wishbone in His kitchen closet. He likes it; therefore, it stays. The whole marvelous collection of stones, skins, feathers, and string exists because at least one lover has never quite taken his eye off it, because the Dominus vivificans has his delight with the sons of man.

Also, please just read the book.

I'm so delighted to hear you reflect more deeply on your love for this book. It IS such a wonder and an all-time fave. I love your thoughts about the cumulative effect of Capon's direct address. So much of the warmth and intimacy of the engagement comes through there.

I bought this book because of you. It's time to reread it. Thanks for the encouragement.