You may have heard that Joan Didion’s estate was auctioned off yesterday. The final total was $1,920,700, all of which was donated to two charities — Columbia Presbyterian Hospital and University, for research and patient care of Parkinson’s and other movement disorders, and the Sacramento Historical Society, to benefit a scholarship at Sacramento City College for women writers. (Didion was born and mostly raised in Sacramento, and when she died last December at age 87, it was from complications from Parkinson’s.)

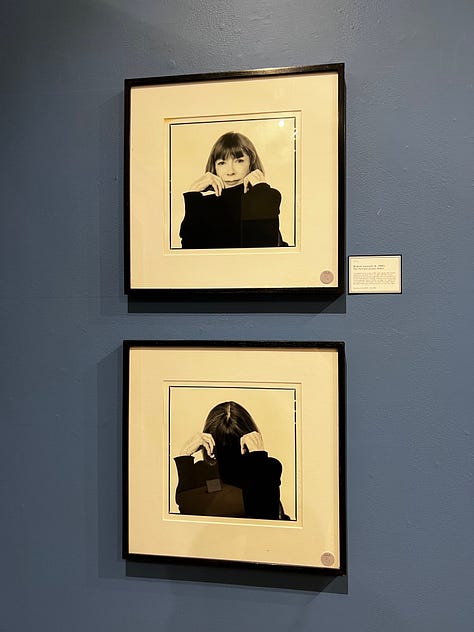

Most of my corner of the Internet spent yesterday marveling over what people would pay for a piece of Joan. A stack of blank notebooks (like, totally blank random little notebooks) went for $900. A novelty apron emblazoned with the words “Maybe Broccoli Doesn’t Like You Either” went for $1200. Her Celine sunglasses, which might rightly be designated as “iconic,” went for $27,000. Photos and artwork by Cy Twombly, Ed Ruscha, Patti Smith, Julian Wasser, and many more artists (including Didion’s daughter Quintana Roo Dunne, who died in 2007) went for enormous and in some cases record-setting sums.

People kept texting me all day about the price the items were fetching. For good reasons. My next book, which is very much in progress, leans a lot on Didion’s work, so I’ve spent my fall poking around in Didion’s life, or at least as much of it is accessible to me. I sold the book about two months before she died, and so I had no way to anticipate how much Didion …. stuff … would be going on this year.

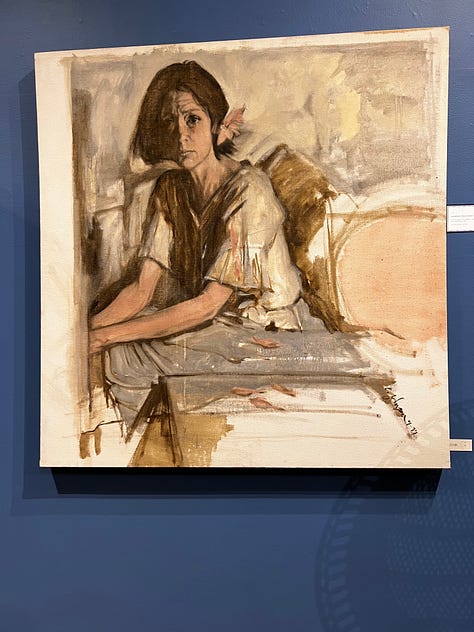

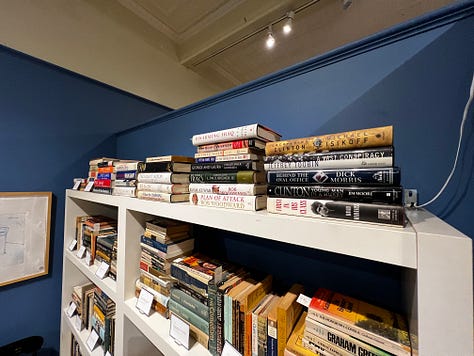

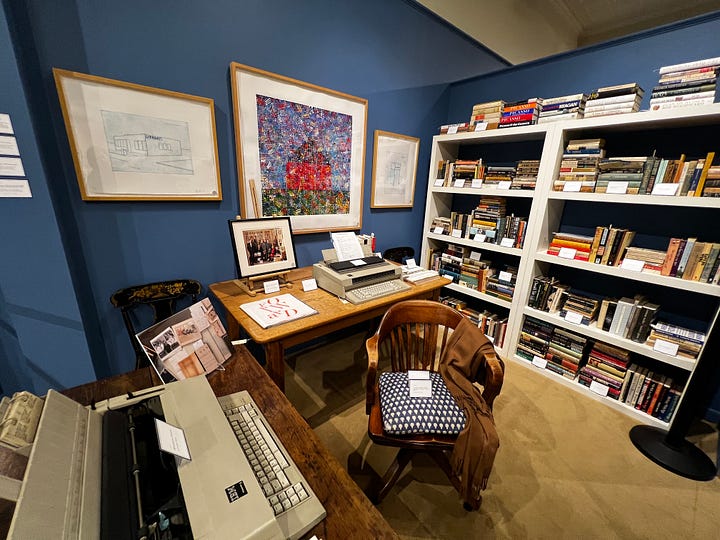

In fact, a scant two weeks ago, on the very day of my 39th birthday, I was in Hudson, New York (about two hours north of New York and a half-hour from where I grew up) to see the estate before the auction. Stair Galleries is on Warren Street, the main drag in Hudson, and they’d set aside the equivalent of two generously-sized New York apartment rooms to display all the items before the auction. I looked at Joan’s art, her couches, her collection of recipe books. Her camel-colored Loro Piana shawl, with a few little stains that looked like drips of coffee. A typewriter with a list of her favorite books shoved into it, scrawled in her utterly unreadable handwriting. Stacks of books about 90s politics that I could identify as research for specific New York Review of Books essays (see her collection Political Fictions). Some Le Creuset cookware, some seashells, dishware, photos you’ve seen everywhere.

I wanted to see all of it, mostly because I have been trying to get inside her head, as best I can, for a long while. I spent four days in Berkeley pawing through her archives there (which end in the early 90s), and her husband John Gregory Dunne’s archives, too. (John’s handwriting is far more legible than Joan’s, and his notes also seem to illustrate a much more self-doubting sensibility, full of scrawled questions to himself. Sometimes you see her notes in his margins.) I went to her memorial service at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine on a hot day in September, with a thousand other people; the part of it that will stay with me always is watching Vanessa Redgrave (who starred in the original Broadway adaptation of Didion’s Year of Magical Thinking) read the last few pages of the book.

I spent several days in LA last month at the Hammer Museum, slowly examining everything in Hilton Als’s show about her. (When I contacted the Morgan Library in New York, the usual resting place for her screenplays, I realized that they’re in LA. Whoops!) And last week, I gave a short talkback following an (inspired) off-Broadway performance of Year of Magical Thinking, starring Kathleen Chalfant, which has been roaming around New York for a month in living rooms and community spaces with intimate audiences.

I’m slightly closer to understanding her, or at least thinking I do — she’s a much funnier and more lighthearted character than a lot of people seem to think. (Consider, once again, the broccoli apron.) As I’ve realized in the process of research, her early work for Vogue, including her film reviews — most of which haven’t been collected — is extremely funny. Later her work grew more serious, but it always carries the wry tone of a woman in full possession of her comic powers. One of her greatest works is a reply to a letter from a reader of the NYRB who didn’t appreciate her 1979 takedown of Woody Allen. His letter was (as these things often are) some combination of haughty, patronizing, and apoplectic; her entire, printed reply was simply: “Oh, wow.” A dour writer could never.

All of this is in my head when I think about the auction; what accounts for the money? Who buys a small stack of empty notebooks for $900 because they belonged, however briefly and perhaps untouchedly, to a writer you admired?

Some of the estate undoubtedly went to museums. The rest, presumably, went to individuals, and I found myself doing that gatekeeping thing where you just assume nobody really gets the object of their fandom the way you, the sober and measured scholar, do. “Sometimes I get the sense that Didion’s rabid fans base it all on two essays, three pictures, and vibes,” I sniped to someone yesterday.

I mean, I know I’m not wrong. I have heard some hilarious interpretations of Who Joan Was and What She’s Known For over the past couple of years, and reading “Goodbye to All That” and “On Self-Respect” and maybe “The White Album” really doesn’t give you the range and depth of her work; she abandoned that mode pretty early and spent a lot of time writing about the American political circus. She had a lot of very politically incorrect opinions, especially in her early years, when she was the kind of libertarian-leaning conservative that loves Barry Goldwater and comes from the West. She never liked the women’s movement and she loved the work of Norman Mailer and Philip Roth. Post-mortem takes that dared readers to “just try cancelling Joan Didion” were silly and hack-ish, but it does strike me, reading her, that if she was more deeply read she’d be more problematic with a lot of her fans.

Anyhow, the point is: You can’t help but watch the Joan Didion auction and think about what Joan Didion would have to say about it. She would describe, in intimate detail, the objects. She would probably look for things people were saying about it, the motivations they had, what it all signified about culture, about some people, at least, being desperate enough to call a piece of a writer their own that they’re willing to pony up absurd amounts of money for objects that don’t even have her handwriting on them. She would see something interesting about our mimetic culture, where we imitate the “iconic” in order to find meaning for ourselves — to find, in her terms, a story to tell ourselves that gives us some reason to keep living.

You can’t buy someone else’s life, though, and you can’t buy your way into someone else’s life. Owning her notebooks or her dictionary or her couch doesn’t make you Joan. On the other hand, though, bringing her items into your own life story can work as a tribute, a way to graft one narrative onto another, and don’t we all do that? We buy tour T-shirts for our favorite band, or jerseys for our preferred team, or develop preoccupations with franchise film stars and influencers. The only thing we know to do is buy them, a little. And that is what makes our world go round.

Didion also wouldn’t really come to a conclusion about this tendency, I don’t think, or at least not one that was easily parsed. Narrativizing our existences — what the TikTok kids call “romanticizing your life,” I think — is the human condition, both an exercise in fooling ourselves and an inescapable part of trying to string together our days. Maybe getting a novelty apron on the wall in the kitchen that belonged to someone we admired and aspired to be is a way of meaning-making, and maybe it’s better than a lot of other ways we do it, or maybe “better” isn’t a thing at all in this case.

The ambivalence at the core of her writing — at least till the 1980s or so — is an essential part of Being Joan. Or being a Fan of Joan. Of being like Joan. Of Buying Joan, I suppose. Of living in the 21st century, where our stuff signifies our selves, where the things we designate as our icons and our idols tell us who we are. We buy ourselves Joan’s things, and try to live.

Enjoyed this? If you’re feeling it, I won’t object if you buy me a cup of coffee. Writers need fuel.

Fantastic piece. Thanks for sharing photos of the sale.

Really love this reflection on Joan and what we leave behind, Alissa.